Born:

28 March 1760

Wisbech,

Cambridgeshire,

England

Died:

26 September 1846

(aged 86)

Playford, Suffolk,

England

Known for:

Abolitionism

1760

Thomas Clarkson was born on the 28th March, 1760 at the site of the Old Grammar School in Wisbech (Now the Conservative Club). Son to Anne and John, he had an elder brother, John. Both boys attended Wisbech Grammar School, where their father was the School Master.

1766-1778

At the age of six, Thomas Clarkson's father died of a fever caught whilst visiting the sick. Forced to leave the school house, the family, which now consisted of three siblings, moved to 8 York Row- just a few streets away.

Thomas continued to attend the Grammar school until he was a teenager, when he left to attend St Pauls School in London, directly opposite St Pauls Cathedral.

1779-1786

Whilst he was later quoted as saying that the Discipline at St Paul's was harsh, he was still able to leave the school with two scholarships for St Johns College, Cambridge, where he gained a BA in 1783.

Clarkson continued his education at Cambridge and in 1785, entered a Latin essay-writing competition that the University of Cambridge that would change the course of his life. The subject for which the essay had to be written was: "Anne Liceat Invitos In Servitvtem Dare?"- (is it lawful to make slaves of others against their will?)

Naivety of the horrors associated with the slave trade was common in Britain and Clarkson spent two months studying the subject. His primary goal in setting out on the venture was to gain literary reputation and "he anticipated nothing but pleasure from the task of marshalling his arguments and polishing his periods."

However, as highlighted by Bryan Edwards in 1819, when Clarkson came to "examine the facts", his focus turned to a more noble cause with his task rendered painful by the horrible nature of the scenes on which his mind was forced to dwell.

Never the less, in June 1785 the resultant essay gained Clarkson first prize and was read out in the Senate House, to generous applause. Returning to Wisbech, Clarkson set about translating and expanding his essay before riding down to London to look for a publisher.

Whilst in London, he met Joseph Hancock who introduced him to a Quaker Committee, formed with a view to promoting opposition to the Slave Trade. The group comprised Quaker Businessmen; George Harrison, Samuel Hoare, James Phillips, Joseph Woods, William Dillwyn, John Lloyd and Dr. Thomas Knowles.

London gave Clarkson access to a wider circle of influential and knowledgeable people, including Granville Sharp and the Rev James Ramsey.

Among his contemporaries, Clarkson became known as the "originator" and during the winter of 1786/87 both he and Richard Philips worked tirelessly on the launch of a campaign.

Within a year, the committee had expanded from 7 to 30 members and included Josiah Wedgwood (Founder of Wedgewood Pottery).

1787-1791

In 1787, Thomas Clarkson once more returned to Wisbech, this time to write "The Impolicies of Slave Trade". The aim of the paper was to show that the slave trade itself was uneconomic.

During that same period, he travelled throughout England, gathering support for the abolition of the slave trade. This continued until 1791, when William Wilberforce introduced the first Bill to abolish the slave trade on the findings of Clarkson's work.

Unfortunately, the bill was defeated 163 to 99 votes. However, both Clarkson and Wilberforce were not deterred and Thomas travelled a further 6000 miles, engaging with the general population. Abolition groups were set up in major towns such as Nottingham, Newcastle and Glasgow and Clarkson encouraged people to join the boycott of West-Indian slave grown sugar.

1787-1791

Again, the motion to abolish the slave trade was put before parliament and once again it was defeated. Due to the War with France the following year, the debate lost traction and both the Public and Parliament lost interest in the debate.

Ill health as a result of a constant workload were starting to take their toll on Clarkson and he moved to the Lake District, purchasing a 34-acre estate. In 1796, he married Catherine Buck and they remained in the Lake District until 1803, when Catherine became ill.

The death of her mother led to her moving back to stay with her father in Bury St Edmunds (Suffolk). Clarkson would later join her, after completion of his book on Quakerism.

1804-1807 - The final push

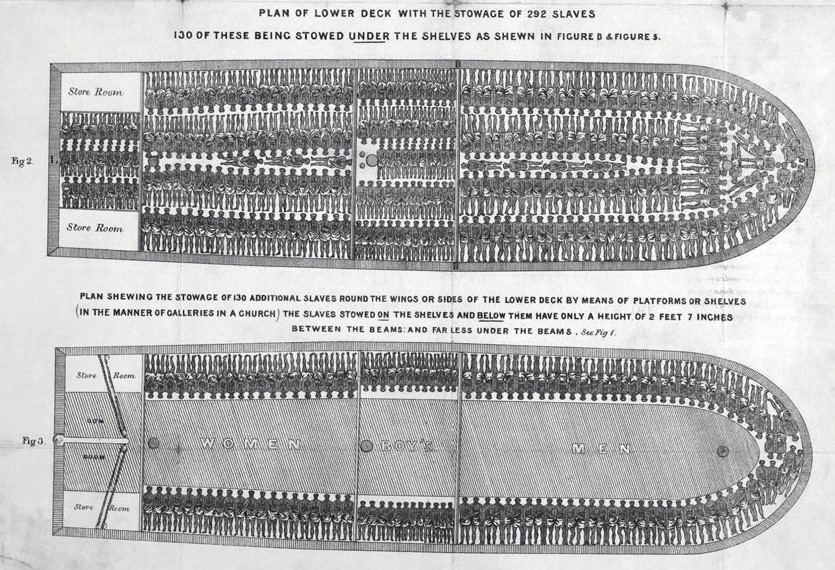

Once again, Clarkson became active in the Anti-slavery Campaign. In 1805, he began another tour of England, gathering support for the movement and in 1807, some two decades after starting the Campaign, a new law was passed by Parliament, placing a fine on the Captain of any ship found with slaves on Board.

Although not an outright abolition, the fine was a significant deterrent, with a cost of £10 for every slave on the ship.

Beyond 1807

Although not an outright abolition, the new law demonstrated that change could be made. In 1814, some seven years after the original law had been passed in Great Britain, Clarkson travelled to France, hoping to persuade the French to abolish the trade.

A year later, whilst in Paris, he met Tsar Alexander I of Russia, who invited Clarkson to write to him, with suggestions as to how the slave trade could be ended.

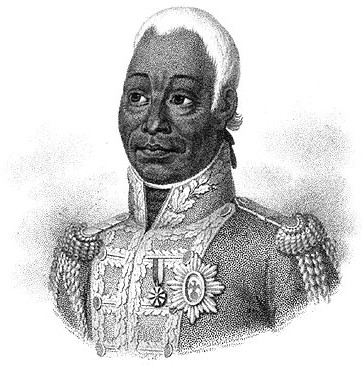

Haiti

By 1815, a revolt in Haiti had seen both British and French forces defeated and the new ruler, Henry Christophe appointed Clarkson as "Haiti's European Advisor". Clarkson would retain this role until the death of Christophe in 1820.

An End to Slavery

In 1823, a new group was formed that aimed to abolish slavery. Both Wilberforce and Clarkson both supported the group and Thomas, aged 63, took to another tour of England, this time covering 10,000 miles, with a view to raising support among the population.

Working with Thomas Buxton, successor to William Wilberforce as leader of the antislavery campaign in the House of Commons, this campaign led to the Slavery Abolition act in 1833.

Although a milestone in the campaign, the Act was not an outright abolition, with an "indentured" service for slaves of 6 years without pay before freedom could be granted.

It would be another 15 years before slavery was completely abolished in Britain.

A life’s work

Clarkson continued his work after the Slavery Abolition Act had been passed by the House of Commons. However, his focus shifted to the United States and during the 1830s and 1840s, he corresponded with leading American Abolitionists and wrote pamphlets on Slavery in America.

Clarkson would live on for a further 8 years (d. 26 September 1846), during which time, he would serve as President of the "British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society".

He was elected to the post in 1840 at the General Convention in London, where he received a standing tribute from 5000 delegates from around the world. The liberator newspaper by William Lloyd Garrison.

Notoriety

His work led to him being visited by Frederick Douglas and William Lloyd Garrison. Garrison was leader of an American Anti-Slavery Society in New England and one of the most prominent and uncompromising American abolitionists of the 19th century.

A prominent figure in American History, Garrison published "The liberator", an anti-slavery newspaper which ran from 1831 until the day all American slaves were free, some 34 years later.

Thomas Clarkson influenced many Abolitionists throughout the world and in 1842 played an influential role in exempting fugitive slaves in Canada from the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, which extradited criminals between Great Britain and the United States.

Of visiting Clarkson in 1846, Frederick Douglass (American) recounted the following in his third autobiography:

"He took one of my hands in both of his, and, in a tremendous voice, said 'God bless you, Frederick Douglass! I have given sixty years of my life to the emancipation of your people, and if I had sixty years more they should all be given to the same cause."

Read more